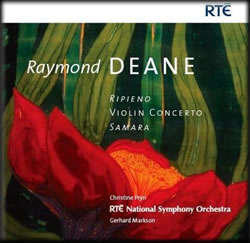

Audio

"Violin Concerto" Christine Pryn (vn-solo), National Symphony Orchestra

Movement I

My Violin Concerto was commissioned by RTÉ for the Danish violinist Christine Pryn, to whom it is dedicated. It was composed in four intense bouts corresponding to its four movements, roughly between April 2002 and May 2003, separated by periods of “extra-curricular” - i.e. political - activity.

Although I have composed a half dozen or so concertante works, only the Oboe Concerto previously (1993-4) bore the straightforward generic title, and the two works are both linked and opposed. To a greater extent than its predecessor, each movement of the Violin Concerto is an odyssey towards its solo cadenza, and the cadenzas recall 19th century models to an almost parodistic extent. Throughout, the tonality of A minor periodically intrudes unexpectedly and threateningly, as do moments of unbridled chaos. If there is a "programme" involved, however, it is a purely musical one, the protagonists being the performers and the musical ideas.

Whereas the orchestra in the earlier work functioned as oppressor and finally “crushed” the exiled soloist, collective and individual have here attained a less fractious co-existence, and the work ends with the soloist’s – albeit slightly demented – liberation. The orchestra itself is much smaller: 10 woodwind, 7 brass, percussion, piano, harp and strings. The overall shape of the work could be described as “two preludes, scherzo, and finale.”

The “soupy” major sixths with which the soloist begins soon turn into the minor thirds of Schubert’s Der Leiermann, the only direct quotation in the work. Here Schubert’s Wanderer, instead of meeting the death that has seemed the inevitable conclusion of his Winterreise, contemplates further wanderings in the company of a strange old man who plies his barrel organ. There follow two hallucinatory variations on this material, the first a kind of Adagio in which the thirds become tenths, the second a wild orchestral orgy without the soloist. A cadenza ushers in an uneasily peaceful conclusion.

The predominantly slow second movement looks at some of the same material,

but subtracts the Schubert. The minor third that is in many ways the emblem

of the entire work here briefly becomes major, a moment of rare sunniness.

The fast third movement dispenses with orchestral strings and harp, and in

many ways functions like a foreign body within the work as a whole. Nonetheless,

it shares essential structural elements with the other movements, notably the

“birthday cell” 2,7,1,5,3 (day, month and year of my birth), which here influences

both rhythm and harmony.

The finale is the longest and most elaborate movement, drawing together all

the strands of the work without being either a “synthesis” or “compendium”

of preceding material. At the beginning and end the piano emerges as a partner

to the soloist, somewhat as in Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso No 5, which

happens to be the work with which Christine Pryn made her début. A double homage

is implied here.